So let's take another crack at this.

About a week or so ago, my Tuesdays friend and I were talking via AOL instant messenger. We're both juniors in college - he's at the University of Minnesota - who are sunk into our majors but are unsure about our future worth to society as professionals. The questionable worth of our chosen trades (graphic design and journalism) and education was the topic of conversation that night. "Tuesday" was telling me that his non-graphic design electives were preparing him better for grown-up life than courses meant to train him for the real world.

Specifically, Tues. referred to his Poetry in Rap classes. According to the university course description, the class series studies the poetry used in rap, African American literature and American culture. (He took the course described in the link last year; now he's the advanced class.) Obviously, it is well outside the required training to be a graphic designer.

He was telling me that the things he's learned in these classes would actually help him be a mildly influential member of society, not one that "just makes logos." That's when this gem of a concept came up:

Everyone is racist and/or prejudice. And the world would be a better place if everyone - the powerful elite and poor underbelly - would openly admit it.That's the idea that started my faulty post. (Maybe I should start listing Tuesday as contributor to this blog, magazine-style.)

Americans would become better people if they recognized and admitted their racism. Sounds radical, really, since judging people on the basis of race or ethnicity usually is considered a bad trait. But here's my interpretation:

Everyone - whites and people of color - is different, thus, by default, everyone holds prejudices. Like it or not, factors such as race, ethnicity, sexuality and age act as divisions for social self-identification. Rather than pretending such identifying characteristics don't exist, people should recognize and embrace them. Lumping everyone into one group can perpetuate inequalities and stereotypes as much as explicit discrimination.Which is what I thought while reading that handout in my newspaper editing lecture. Robert Maynard likened the identifying factors of race/ethnicity, gender, age, class and geography to the geological faults that cause earthquakes. Here's his quote again:

"The society is split along five faults, and we try in vain to paper them over, fill them in or pretend they aren't there. ... (These) underlying forces, like those in the center of the earth, will thwart us until we come to see out differences as deep, but completely natural things, as natural as geologic fault lines. We don't have to resolve our differences. We can agree to disagree."As previously posted, I'm on board with Maynard. But I don't think his agree to disagree philosophy is correctly applied. Or maybe its not applied at all for that matter. Efforts to be politically correct or tasteful are often so over done that the faults are glossed over, painting the picture that everyone is homogeneous and equal. Taking out the identifying characteristics results in bland and inaccurate writing.

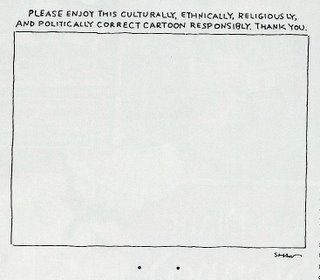

Just by chance, I saw this cartoon in the Feb. 27 issue of The New Yorker. I realize that it's actually a commentary on the cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad, but it kind of conveys my point.

With all that said, I'd be neglectfully ignorant if I didn't recognize the value of journalists and bloggers to be unobtrusive, sensitive and tasteful. The freedom to be offended is implied in freedom of speech, and free speech applies to the offenders and the offended. In the short term, all those efforts to safeguard save writers, publishers and readers lots of headaches.

So here comes the dilemma again. Which is better: editing for across the board "equality" or including the "unequal" differences by which define ourselves? Which causes more offense, and which causes more social ills?

I'm still not sure.

2 comments:

I would agree that the starting place for any productive discussion of race or any other socially-charged category is an admission that, yes, we all (by virtue of living in the culture we live in) are prejudiced. And not in order to stay at that place, but to examine those prejudices and move forward. I guess I'm not as certain what that should mean for journalism. "Offensive" writing can certainly do a lot to replicate prejudices. Does it have potential for dislodging them, too? I guess I have a hard time seeing it, but maybe I'm not looking from the right angle.

Maybe I should explain my angle a little better. By no means am I suggesting that journalists, bloggers, writers in general, use racial slurs or anything of that nature in his or her work. But in trying to keep such material out of writing, all references to race, class, gender, etc. are often eliminated, thus prepetuating stereotypes through virtually ignoring them.

Take the Missourian's style procedure for including a crime suspect's race. "BEFORE we publish the race of a suspect," the style book says, "we will make sure the description includes at least THREE other identifying characteristics, such as weight, height, hair, scars and tattoos." Why is it necessary to have those other three characteristics? It's often hard for police to get that specific of a description of an at large suspect, so race is often left out of the description. In leaving it out though, the Missourian is upholding standard stereotypes. Statistics and public opinion show that most crimes, or at least people believe most crimes, are committed by people of color. Without mentioning that indicator, the paper is just letting its readers ignorantly keep that opinion. (And, since this city is dominated by whites, assuming a crime is committed by a person of color is probably incorrect.)

A side note: interestingly, the style book does not include a gendered entry similar to the one above. Does that mean that its always okay to include a suspects gender? Why should there be a specific explanation for racial fault lines and not one for gender, class, geography or age?

Post a Comment